Mayfly numbers drop by half since 2012, threatening food chain

Mayflies, which form swarms in the billions that are visible on weather radar, are in steep decline, mirroring the plight of insects worldwide.

BY DOUGLAS MAIN

PUBLISHED JANUARY 20, 2020

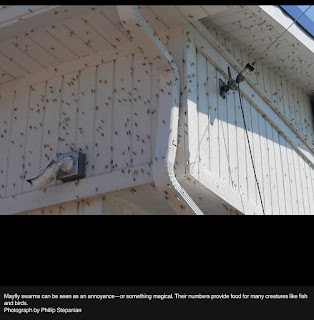

Every summer, mayflies burst forth from lakes and rivers, taking to the skies of North America. These insects, which are particularly abundant in the northern Mississippi River Basin and Great Lakes, live in the water as nymphs before transforming into flying adults. They synchronize their emergence to form huge swarms of up to 80 billion individuals—so massive that, in waterside towns, they are sometimes scooped up with snowplows.These insect explosions provide food for a wide variety of animals, from perch and other commercially important freshwater fish to birds and bats. But new research shows that mayflies are in decline. Since 2012, mayfly populations have declined by more than 50 percent throughout the northern Mississippi and Lake Erie, likely due to pollution and algal blooms, according to a study published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We were really surprised to see that there was a decline year after year,” says lead author Phillip Stepanian, a bio-meteorologist at the University of Notre Dame. “That was really unexpected.”

These swarms are so big and thick that they appear on weather radar used to track rain and snow, and for a long time, meteorologists ignored these signals as a type of “noise,” he says. But Stepanian, who was trained as a meteorologist, realized these signals could provide useful information about populations and movements of animals like birds and insects, including mayflies.

In the paper, Stepanian and colleagues used radar to estimate mayfly populations, validating the method by comparing it with numbers of mayfly nymphs found in the sediment at the bottoms of rivers and lakes.

The study revealed that between 2015 to 2019, populations of burrowing mayflies in the genus Hexagenia declined by an incredible 84 percent in western Lake Erie. In the nearby northern Mississippi River Basin, from 2012 to 2019, they declined by 52 percent.

These dropping populations are significant because the insects are an important link in the food chain, serving as prey for a variety of predators. They also transfer tons of nutrients from the water to the land, a valuable ecological service.

“Mayflies serve critical functions in both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems,” says Jason Hoverman, an ecologist at Purdue University who wasn’t involved in the paper.

“Because of their important role as prey, reductions in their abundance can have cascading effects on consumers throughout the food web.”

A CONCERNING FALL

There are several possible reasons for the decline. First, levels of neonicotinoid pesticides have risen in recent years in Lake Erie and many freshwater systems in the Midwest. The chemicals, which are toxic to many insects, have been measured in Great Lakes tributaries at levels 40 times greater than protective levels set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Aquatic Life Benchmark, according to a 2018 study.

Second, Lake Erie especially is beset by algae blooms, which are caused by excess runoff of fertilizers and other nutrient-laden pollutants.These blooms can result in oxygen-depleted “dead zones,” which are toxic for bottom-dwelling creatures like mayfly nymphs. Third, water temperatures are warming as the climate changes, potentially interfering with the animal’s life cycle and possibly decreasing circulation of oxygen in the lake.

Mayflies serve as an overall indicator of water quality, says Kenneth Krieger, emeritus director of the National Center for Water Quality Research at Heidelberg University, who’s studied Lake Erie mayflies for many years. That’s why their decline is a reason for concern, he says.

“It is likely that other aquatic insect species may be undergoing the same declines for the same reasons,” adds Francisco Sanchez-Bayo, an ecologist at the University of Sydney in Australia. “The inevitable consequence is the decline of populations of insect-eating birds, frogs, bats, and fish in those regions,” he says.

INSECT APOCALYPSE

Unfortunately, they’re not alone: Studies around the world have shown alarming declines of a wide variety of insects. A study published in the journal Biological Conservation in April suggested that 40 percent of all insect species are in decline and could die out in the coming decades. (Learn more: Why insect populations are plummeting, and why it matters.)

Neonicotinoids are notorious for their toxicity to aquatic insects, and mayflies appear to be particularly susceptible to them, according to the paper. Another recent study found that neonicotinoid use in a Japanese lake led to the decline of water-dwelling invertebrates, and a subsequent collapse in populations of two commercially important fish species that fed upon them.

Mayfly populations have dropped in decades prior and then recovered, but the consistent and continued decline in these last few years is troubling, Hoverman says.

“This research adds to the growing list of studies that show substantial declines in insect populations,” he says.

_

Follow on Instagram

Follow on Instagram